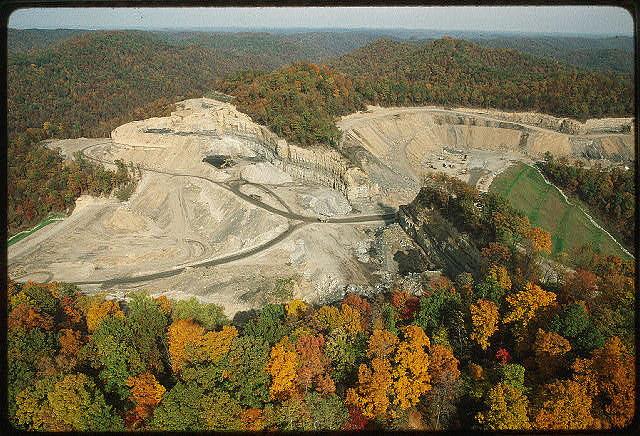

Aerial view of mountaintop removal and reclamation landscapes. Public domain photo from the Library of Congress.

Annapolis, Md — Surface mining and its most destructive practice, mountaintop removal, are now the dominant drivers of land use change in the central Appalachian United States. These mining activities have destroyed hundreds of waterways by exacerbating pollution, clearing vegetation, and burying headwater streams with rock and soil (known as “overburden”).

Although coal companies are required by federal law to avoid, minimize, and mitigate impacts of mining operations so that there is no significant harm to the environment, a new study by National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center (SESYNC) researchers finds that these companies are failing to hit the mark. The report was recently published in Environmental Science & Technology, and the large dataset compiled and analyzed by the researchers is publicly available online at: http://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.2d504

Authors Margaret Palmer, SESYNC Executive Director and Professor at the University of Maryland, and Kelly Hondula, SESYNC Faculty Research Assistant, collected information on 434 mitigation projects throughout West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia. They found that criteria for projects to be deemed successful do not correspond with scientific standards for restoration.

The problem lies in regulation that addresses form instead of function. Restoration standards are generally limited to visual structural measures—and it’s relatively easy for a project to be in compliance when the only requirement is to rebuild a stream that resembles in length, shape, and pattern a natural waterway gutted by mining operations. However, structural monitoring data cannot speak to whether the mitigation project has restored the vital physical, chemical, and biological processes that occur in ecosystems, such as temperature and oxygen regulation and biodiversity.

“Environmental impacts to streams by mountaintop mining are known to be primarily due to toxic levels of metals and salts, but most mitigation projects are evaluated on the basis of visual assessments,” explains Palmer. “However, this study indicates that even in places where a mitigated stream ‘looks’ better over time, the restoration actions are insufficient to address biological and chemical water quality problems.”

Structural requirements for mitigation, say the authors, are just not good enough.

“It’s not unlike trying to understand something about a person’s income and cash flow by asking how much money they have in their pocket,” Hondula adds. “These are crude assessments that cannot predict whether the ecosystem can recover ecologically.”

In a minority of cases (fewer than a third), companies were required to collect biological or chemical data, giving clues about stream function. These data tell a story that doesn’t end with “in compliance.”

“We found that maybe structural assessments indicate habitat improvement from poor to sub-optimal,” says Palmer, “but that the water chemistry was still tanking, and the biological score was within the impaired level for that state. And yet, many project summary statements say, ‘the stream appears to be moving towards being restored.’ It’s as if they are ignoring the data.”

In many cases, ignoring the data is acceptable from a regulatory perspective, because only eight of the 434 projects had criteria requiring an improvement in biological or chemical data. In other words, the only requirement was to collect and report the data—not to make things better.

“It’s baffling,” Hondula said. “These projects are reporting water quality data that is clearly inhospitable to aquatic life, according to a wide body of ecological scholarship. And yet they go on to conclude that the project is progressing or likely to meet its goals, because the mitigation requirements are insufficient.”

Only 100 of the 434 mitigation projects contained at least three years of monitoring data. The remaining 334 projects are either relatively new or have only been approved and have yet to begin. Palmer anticipates that some critics will point to alleged improvements in restoration techniques to dispel the report’s conclusions.

“We expect that the reaction might be, ‘the results data are from projects that were permitted 10 or more years ago. We do things differently now, and things will be better,’” she said. “So we pulled a sample of recently-permitted projects to see what methods they’re proposing to mitigate, and they’re exactly the same. So there’s no reason to believe the outcomes will change, and there’s no reason to believe the health of these streams will get any better.

“Ultimately, this study adds to a growing body of evidence that we, as a nation, need to revisit how we’re dealing with mitigation requirements, enforcement, and compliance,” added Palmer.

The National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center, funded through an award to the University of Maryland from the National Science Foundation, is a research center dedicated to solving complex problems at the intersection of human and ecological systems.

Media Contact

Melissa Andreychek

mandreychek@sesync.org

(410) 919-4990